Sanctions, De-risking, or overcompliance? How to address the problems of the financial sector regarding Venezuela?

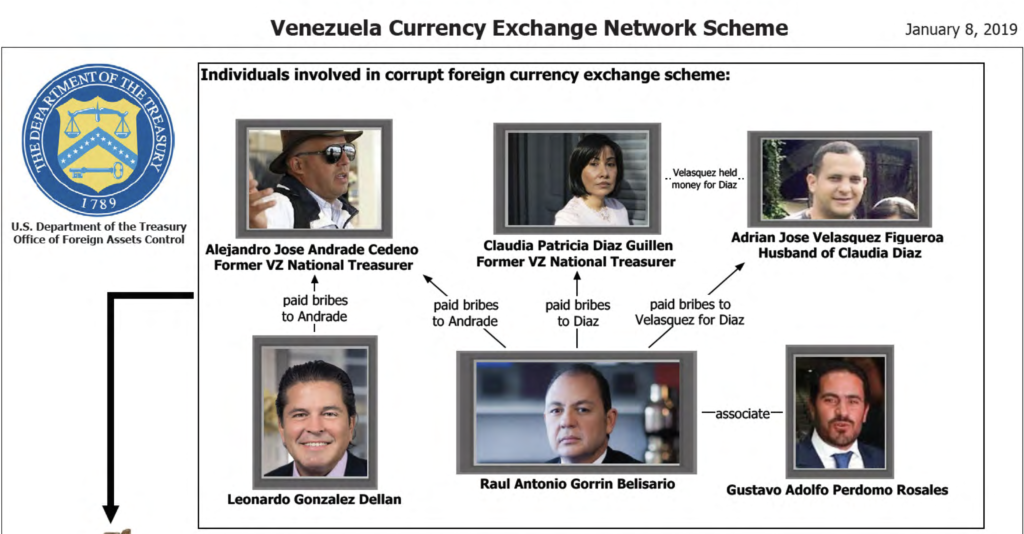

Source: OFAC

Venezuela is a targeted state of the U.S. sanction policy -in one of the most restrictive frameworks currently in place. The U.S. Government implemented that policy in 2014 only regarding persons included in the SDN list, but since 2017 has escalated to restrict transactions of the Government of Venezuela. Executive Order 13884, dated August 5, 2019, adopted a comprehensive regime that prohibited all transactions of the Government of Venezuela in the U.S. or with U.S. sanctions. Also, the U.S. Government adopted a discretionary policy to sanction -only regarding the U.S.- foreign persons or firms that were collaborating with the Government of Venezuela (usually known as secondary sanctions).

The Venezuelan sanction programs have been under a contentious debate, particularly regarding their implications for the Venezuelan economy. As the U.S. Congress recently concluded, the sanction policy is part of bi-partisan efforts to promote a negotiated solution for the Venezuelan crisis, and its effectiveness has been under debate.

Due to the bi-partisan support of the U.S. policies regarding Venezuela and the long tradition of the sanction programs in the foreign relation policies of the U.S. (particularly under the current situation of Ukraine’s invasion), we can assume that any significant change in Venezuela sanction policy -including “lifting” sanctions or revoking the Executive Orders in place), is not an easy solution.

Considering this scenario, and from a pragmatic perspective, it is better to identify specific constraints over economic and financial transactions in Venezuela and design solutions within the current sanction framework. That approach is particularly relevant regarding overcompliance.

The financial sector -in Venezuela and abroad- is subject to national and international financial intelligence regulations, preventing risks in terms of money laundering, financing of terrorism, and other illicit funds (AML/CFT). Financial institutions have several duties regarding compliance with that regulation, particularly preventing transactions that could expose the institution to fines and criminal charges. Regarding suspicious transactions, the complaint officers could prefer to suspend transactions in a cost/benefit analysis to avoid any risks. That is, under uncertain environments, there is a tendency to increase compliance, resulting in an overcompliance that restricts transactions that are not prohibited.

Regarding Venezuela, overcompliance -more than the direct consequences of sanctions- can explain the constraint financial institutions face regarding Venezuelan transactions.

The Executive Order 13884 does not prohibit transactions between the private sector. For instance, a corporation in Venezuela can import goods from the U.S. and even pay for the import by a transfer to a U.S. account. Likewise, a Venezuela NGO can have a bank account in the U.S. to receive financing for its humanitarian activities. Neither of those transactions are prohibited because they do not involve the Government of Venezuela.

That´s the theory. The practices could be very different, as a result of the overcompliance. Any transaction related to Venezuela is considered a risky operation that leads to reinforcing compliance. Financial institutions sometimes prefer not to allow transactions until the legal situation is clarified. That result in an ambiguous status in which the institution “blocks” the funds until OFAC clarify the situation, although OFAC cannot intervene in transactions not prohibited by sanctions.

The direct cause of overcompliance is not sanctions but the overall evaluation of the institutional risks regarding Venezuela. Lifting the sanctions, then, will not solve that problem.

Another problem related to Venezuela is the “de-risking“, that is, the financial institutions’ decision to terminate contractual relationships with Venezuelan individuals or companies as a more efficient option than managing the risk. Based on a cost-benefit analysis, the financial institutions can conclude that the risk management costs may not be offset by the volume of business from Venezuela.

We cannot deny that sanctions have aggravated the risk regarding Venezuela because compliance officers have extreme diligence to verify that a financial transaction is not prohibited. But the constraint is caused by the perception regarding sanctions -not by a direct application of the prohibitions derived from Executive Order 13884.

That explains why corporations with licenses that authorize prohibited transactions still face problems working with the financial sector. Those problems are not consequences of sanctions -that do not apply- but of overcompliance.

Only identifying the binding constraint that prevents everyday financial transactions with Venezuela will result in an accurate strategy to solve the problem. Focusing only on “lifting the sanctions” does not consider the issues related to overcompliance and de-risking, which -once again- will not disappear even if sanctions are “lifted”, for instance, by a license. Besides, as explained, “lifting the sanctions” does not look like a probable objective in the near future.

However, it is possible to design solutions to the problems derived from overcompliance and de-risking, even under the current sanctions framework. That will require a joint effort between Venezuelan and foreign banking institutions, the private sector, and U.S. organizations such as FINCEN and OFAC.

Overcompliance and de-risking are a consequence of the perception regarding the Venezuela institutional environment. Creating more confusion with a general solution -such as “lifting the sanctions”- does not contribute to a straightforward and technical solution to the problems caused by overcomplicate. It is time to tackle the binding constraint: the perception that leads to overcompliance and, in extreme cases, de-risking.